The development of generic versions of innovator medicines is a global public health need. Generic medicines have the potential to support increased supplies of life-changing treatments and cures, reduce risks associated with potential medicine shortages, and decrease costs, making therapies more affordable to larger segments of the global population. The same potential benefits can apply for so-called “complex generics” (CGx), which are generic drug products that have a complex active ingredient, formulation, dosage form, route of delivery, or are part of a drug/device combination.1 Although CGx can add to development complexities, global regulators and standard-setting organizations can help address related challenges.

Ensuring quality is essential

Regulatory agencies and pharmacopeias around the world establish guidelines and requirements for generics manufacturers to follow in the manufacturing, testing, and labeling of their drug products to ensure they meet the same quality standards as the innovator product. Quality standards in particular help ensure medicines are safe, work as intended, and are available when needed, no matter the company producing them or where they are made. While drug makers rely on USP standards for the clarity they provide on product quality specifications, regulators also look for manufacturer adherence to USP standards to indicate no additional validation of quality testing methods may be needed. This enables efficient regulatory processes, timely product reviews, and faster market access. In fact, USP documentary standards are recognized in U.S. law and in 50+ other countries, while USP physical Reference Standards are used in 150+ nations.

Guidelines and requirements for generics manufacturers enforced by regulators facilitate demonstration of therapeutic equivalence (TE) while reducing the need for extensive clinical trials. For the generic versions of the majority of small molecule drugs formulated as oral solid dosage forms and aqueous injections, demonstration of TE typically follows standardized procedures that facilitate development, registration, and marketing approval.

Complex generics pose additional challenges

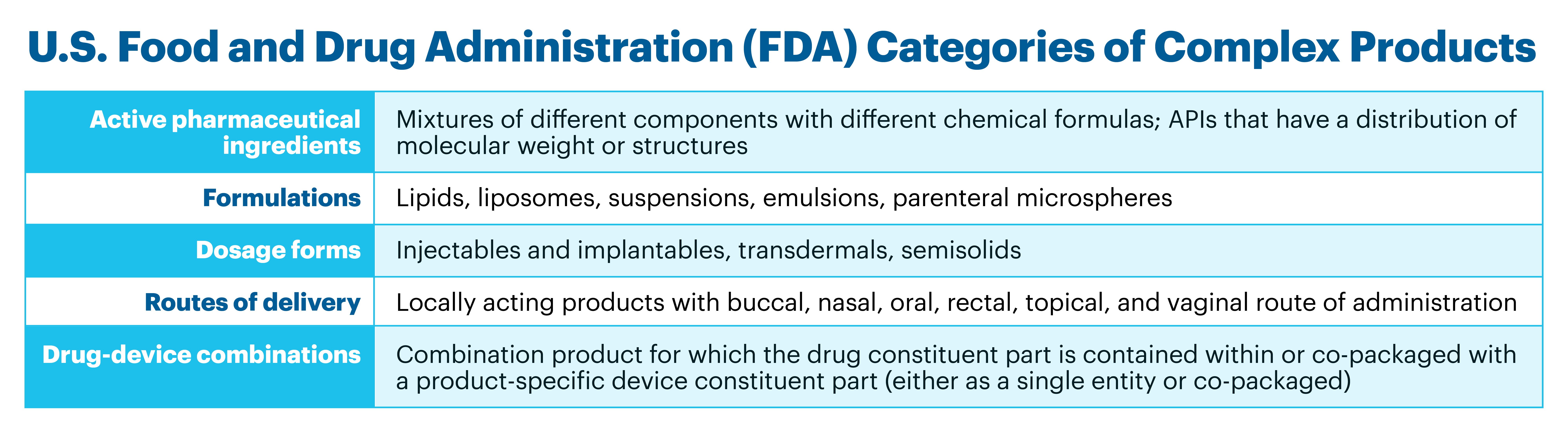

However, contrary to the case of simple generics, the development and approval of CGx – generic versions of numerous non-biological complex products (NBCPs) – is more challenging because of the difficulties in demonstrating their TE. The term NBCP is used since non-biological complex drugs (NBCDs) have been used for both complex APIs and the various types of complex finished products referred to by the U.S. FDA.1-3 Examples of NBCPs are shown below in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Classification and examples of complex products, as defined by the U.S. FDA1

Even the requirements for TE for different types of products within individual NBCP categories may not be the same. To address this challenge and to support the development of generic versions of NBCPs, as well as assist manufacturers in planning of required studies for approval, the U.S. FDA publishes Product Specific Guidances (PSGs).The value of U.S. FDA’s PSGs to accelerate approval of CGx is attested in the Orange Book, where one can follow – in many cases – the correlation in time between the publication of a PSG and the subsequent approval of the corresponding CGx. PSGs are not only important for market expansion, but also because they facilitate prompt development of relevant quality standards that can support registration and a more effective surveillance of the efficacy, safety, and quality of approved CGx.

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) also recognizes that additional in vivo studies – beyond reliance on innovator studies – are required for the development and approval of generic versions of certain NBCPs, and they classify and provide guidance under the category of hybrid medicines.4

Approaches by global regulators vary

Beyond the U.S. FDA and EMA, at websites from most regulatory agencies around the world, there is no explicit mention of the U.S. FDA categories as complex products and/or of guidelines for development and approval of their generic versions. The lack of specific information and/or guidelines is surprising given the fact that NBCPs – for non-generics, as well as, in many cases, their generic versions – are available on the market in those countries.

USP recently performed an in-depth study of the landscape of NBCPs in ten countries from Africa, Asia, Europe, and Latin America, and partial findings of the study will be presented this month at poster session II (P225: Global Regulatory Landscape of Complex Generics) of the DIA 2023 Global Annual Meeting. Our research verified that these countries market NBCPs, including CGx, within the various categories defined by the U.S. FDA, and confirmed that there is no explicit mention of NBCPs as an entity that itself requires unique regulatory approaches. Though quality specifications were identified for some complex products and there are certain guidelines that could apply to a narrow number of products within a category, the agencies in the assessed countries do not develop any specific guidance to address the unique needs of individual products, as the U.S. FDA does. When NBCPs containing specific APIs were assessed, the same two countries, India, and Turkey, had the larger number of products and the larger number of related national/regional pharmacopeial standards.

The U.S. FDA and EMA established a collaboration in 2021 enabling the early exchange of views on the topic between the two agencies and industry applicants,5,6 and it is anticipated that this effort will facilitate inter-agency harmonization of regulatory requirements. Though it may be too early to envision harmonization for certain CGx at a global level, it is still warranted to advocate for regulatory convergence in other countries with the U.S. FDA and EMA. While regulatory harmonization refers to the process of aligning technical guidelines among participating authorities in multiple countries to achieve uniformity, regulatory convergence refers to the voluntary process of gradually aligning regulatory requirements in different countries or regions over time.7,8 Convergence in this case would facilitate registration of novel CGx in more countries and consequently broaden patient access to the benefits they can bring, in particular for countries with large domestic markets and high disease burdens.

Explicit recognition by regulatory agencies worldwide of the particular complexity of NBCPs including CGx, will be an important step towards addressing the need for proper guidelines regulating them, ensuring standardization, streamlining registration processes, and enhancing patient accessibility to these critical therapies.

1U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2022. MAPP 5240.10.

https://www.fda.gov/media/157675/download?utm_medium=email&utm_source=govdelivery

(accessed on June 12, 2023)

2Daan J.A. Crommelin, Vinod P. Shah, et al. 2015. European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences, 76: 10–17.

3U.S. Government Accountability Office. 2017. GAO-18-80. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-18-80

(accessed on June 12, 2023).

4https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/human-regulatory/marketing-authorisation/generic-hybrid-medicines

(Accessed on June 12, 2023)

5https://www.fda.gov/drugs/generic-drugs/fda-ema-parallel-scientific-advice-pilot-program-complex-generichybrid-products

(accessed on June 12, 2023)

6Thor, S., Vetter, T., Marcal, A. et al. 2023. EMA-FDA Parallel Scientific Advice: Optimizing Development of Medicines in the Global Age. Ther Innov Regul Sci, Mar 4:1–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43441-023-00501-9 (accessed on June 12, 2023)

7Regulatory harmonization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. WHO Drug Inf. 2014;28(1):3–10. (https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/331104, accessed June 12, 2023).

8Regulatory harmonization and convergence. Silver Spring (MD): US Food and Drug Administration; 2015. (https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/international-activities/regulatory-harmonization-and-convergence, accessed June 12 2023).